Joel Daniel Phillips

Joel Daniel Phillips is an American artist living in Tulsa, Oklahoma, whose work centers on questions of truth and historical amnesia—the veracity of the stories we tell ourselves about our collective pasts. His work has been selected three times for the Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC.

Phillip’s work has been in notable museum exhibitions at the National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC; Orlando Museum of Art; Joel Daniel Phillips: It Felt Like The Future Was Now, Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa; The Outwin 2016: American Portraiture Today, Tacoma Art Museum; Art Museum of South Texas, Corpus Christi; Charcoal Testament: Drawings by Joel Daniel Phillips, Fort Wayne Museum of Art; Dorothea Lange’s America, Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa; Ackland Art Museum, Chapel Hill; Western Art Pavilion Inaugural Exhibition, Denver Art Museum. Museum collections: Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC; Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa; Phillips Collection, Washington, DC; Ackland Art Museum, Chapel Hill; Urban Nation Museum for Urban Contemporary Art, Berlin; West Collection, Oaks; Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa; 21c Museum Hotels, Louisville; Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento; Fort Wayne Museum of Art; Denver Art Museum. Select pieces from “Killing the Negative” are in the collection of 21c Museum Hotels, the Philbrook Museum of Art, and the Crocker Art Museum.

Phillips has been an artist in residence at Ramfjord’s Kunstkollectiv, Oslo, Norway, a recipient of The Jaunt travel project, Morocco, and is currently a Fellow at the Tulsa Artist Fellowship in Oklahoma. The first presentation of his work with Catharine Clark Gallery was at EXPO Chicago 2024.

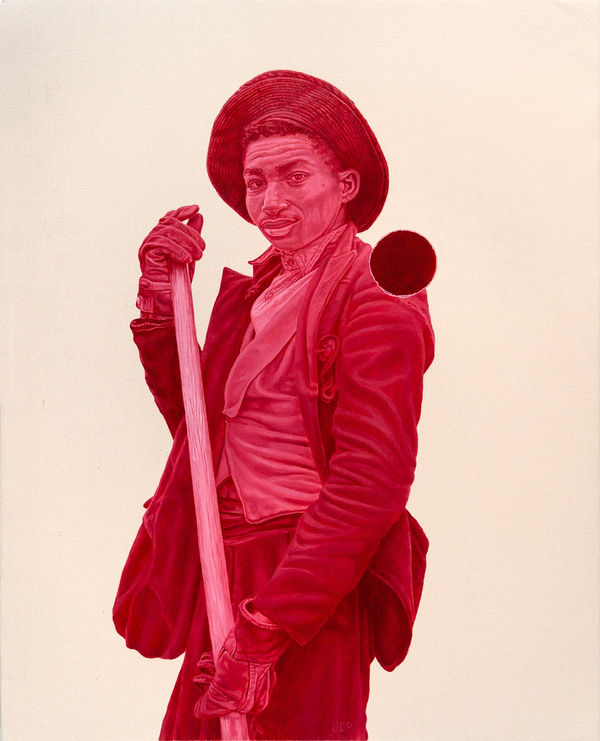

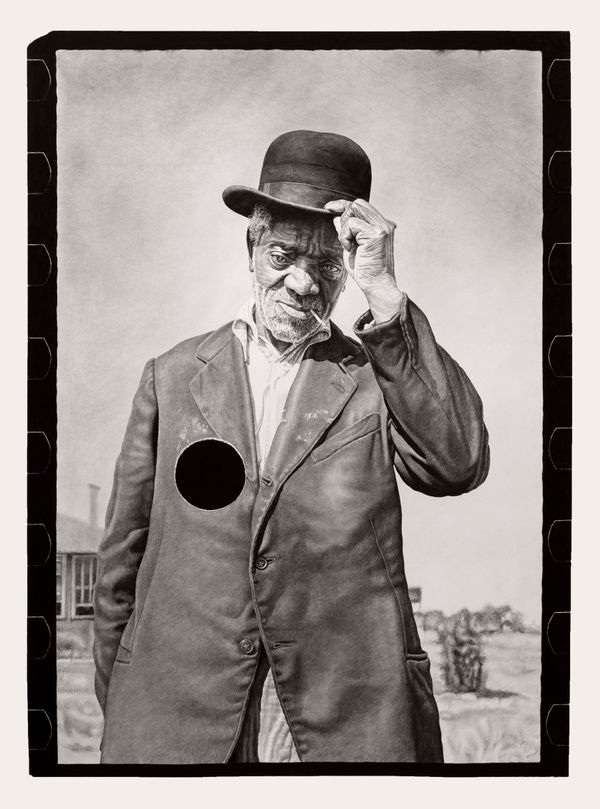

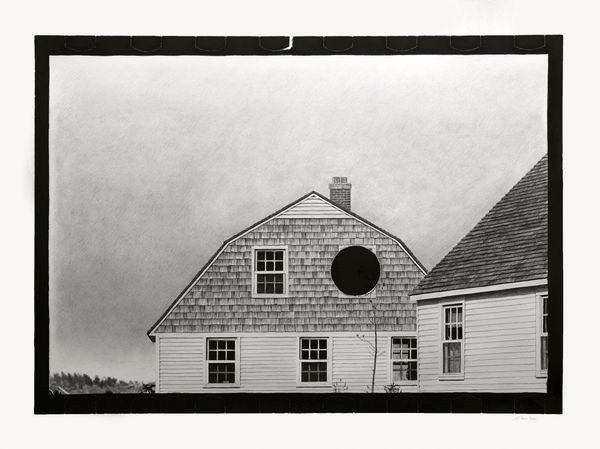

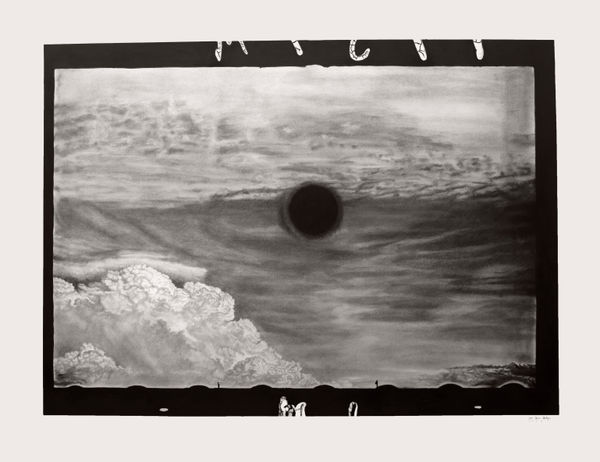

"Killing the Negative": The works in “Killing the Negative” respond to a subset of the Farm Security Administration’s (FSA) foundational commissioned photographs made during the Great Depression. The collaboration explores intersections of representation, truth, and power by re-contextualizing archival material. They walk the line between describing a shared, forgotten history, current questions of race, class, labor and compensation, land ownership, stratified socioeconomics, and ecological protection, and prophesying a terrifying, future.

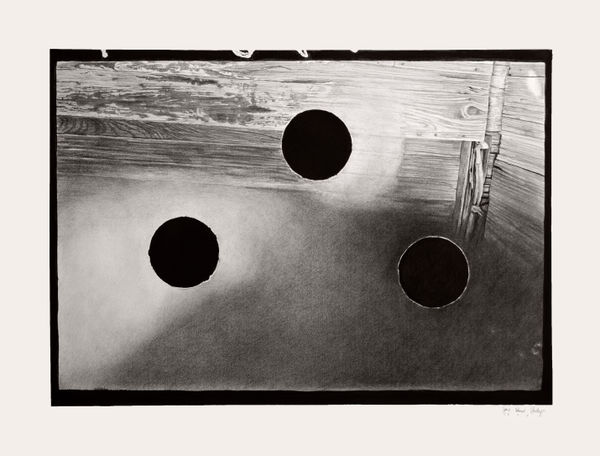

For the series “Killing the Negative,” Phillips responded to what is not as known about the process by which the photographs made under the FSA were selected for publication. Through a deep dive into the archive, Phillips learned about who made the choices and what happened to the images (the negatives) for the photographs that were deemed unworthy of publication. The head of the FSA in this era was Roy Emerson Stryker (b. November 5, 1893 – d. September 27, 1975). It was he who “killed” images he felt were unsuitable for publication by punching a hole in the original negative. The current political debates about race, class, labor, compensation, land ownership, socio-economic stratification, and ecological protection resonate deeply with issues of that era embedded in the original censored FSA photographs.

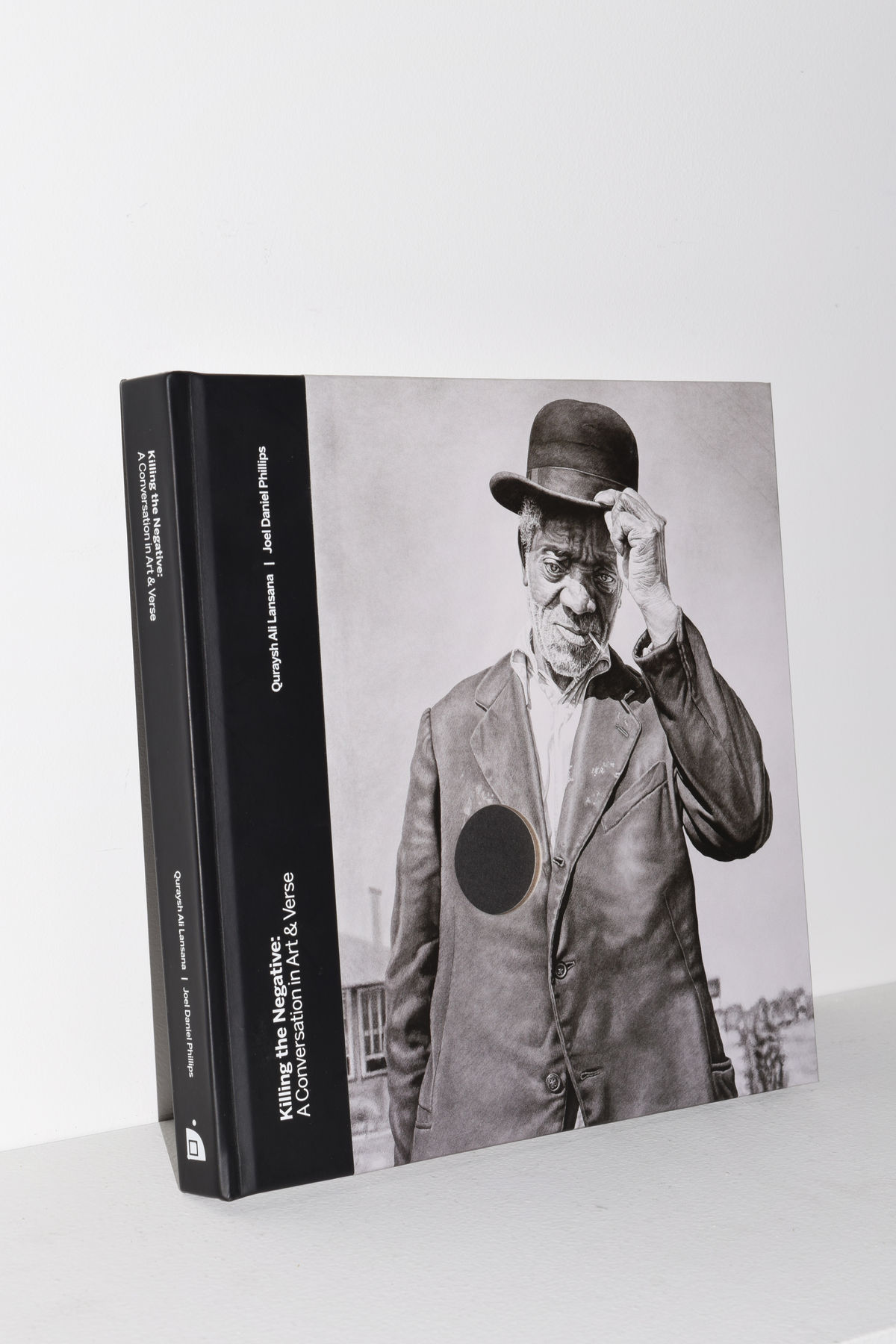

This discovery of a “killed negative” led Phillips and poet Quraysh Ali Lansana into a multi-year collaborative project and book: Killing the Negative: A Conversation in Art & Verse, with introductory essays by Susan Green, Marcia Manhart Endowed Associate Curator for Contemporary Art & Design at the Philbrook Museum of Art, and Erica X. Eisen. Contributing poets include US Poet Laureate, Joy Harjo; North Carolina Poet Laureate, Jaki Shelton Green; Randall Horton; Rose McLarney; Ken Hada; Moheb Soliman; and Candace G. Wiley. The project is an ekphrastic rejoinder to FSA Director Stryker’s once little-known practice of destroying the photographs he found unappealing. As an ongoing collaboration, “Killing the Negative” addresses the gaps in the narrative left by censorship, introducing new images and words into the spaces created by Stryker’s hole punch. Within the project, Stryker’s destructive editing process serves as a larger commentary on truth and the accuracy of the historical record, highlighting the flaws in our reliance on this record and emphasizing the power that a single individual had in shaping the collective understanding of an entire nation. The writers contribute interventions of text, sound, and breath, giving voice to the subjects of these damaged negatives. In each collaboration, poet and artist work together to fill the void left by heavy-handed government-directed practices, creating an entirely new conversation about power, representation, and the shaping of America’s history.

-

Flour Sack #1, 2025View more details

Flour Sack #1, 2025View more details -

Flour Sack #2, 2025View more details

Flour Sack #2, 2025View more details -

Flour Sack #3, 2025View more details

Flour Sack #3, 2025View more details -

Killed Negative #106, 2025View more details

Killed Negative #106, 2025View more details -

Killed Negative #107, 2025View more details

Killed Negative #107, 2025View more details -

Killed Negative #109, 2025View more details

Killed Negative #109, 2025View more details -

Killed Negative #110, 2025View more details

Killed Negative #110, 2025View more details -

Killed Negative #111, 2025View more details

Killed Negative #111, 2025View more details -

Killed Negative #112, 2025View more details

Killed Negative #112, 2025View more details -

Killed Negative #114, 2025View more details

Killed Negative #114, 2025View more details -

Killed Negative #115, 2025View more details

Killed Negative #115, 2025View more details -

Killed Negative #116, 2025View more details

Killed Negative #116, 2025View more details -

Killed Negative #104, 2024View more details

Killed Negative #104, 2024View more details -

Killed Negative #105, 2024View more details

Killed Negative #105, 2024View more details -

Killed Negative #97 / After Unknown Photographer, 2024View more details

Killed Negative #97 / After Unknown Photographer, 2024View more details -

Killed Negative #13, 2023View more details

Killed Negative #13, 2023View more details -

Killed Negative #35 / After Arthur Rothstein, 2021View more details

Killed Negative #35 / After Arthur Rothstein, 2021View more details -

Killed Negative #36 / After Theodor Jung, 2021View more details

Killed Negative #36 / After Theodor Jung, 2021View more details -

Killed Negative #48 / After Unknown Photographer, 2021View more details

Killed Negative #48 / After Unknown Photographer, 2021View more details -

Killed Negative #49 / After Unknown Photographer, 2021View more details

Killed Negative #49 / After Unknown Photographer, 2021View more details

-

Paris Photo 2024

Booth D39 | Joel Daniel Phillips + Stephanie Syjuco November 7 - 10, 2024Paris Photo 2024 | Booth D39 Joel Daniel Phillips + Stephanie Syjuco Catharine Clark Gallery returns to Paris Photo with a two-artist presentation of work...Read more -

EXPO CHICAGO 2024

Booth 344 | Navy Pier April 11 - 14, 2024For EXPO CHICAGO 2024, Catharine Clark Gallery presents the work of Sandow Birk, Joel Daniel Phillips, Stephanie Syjuco, and Marie Watt. Their artworks delve into...Read more