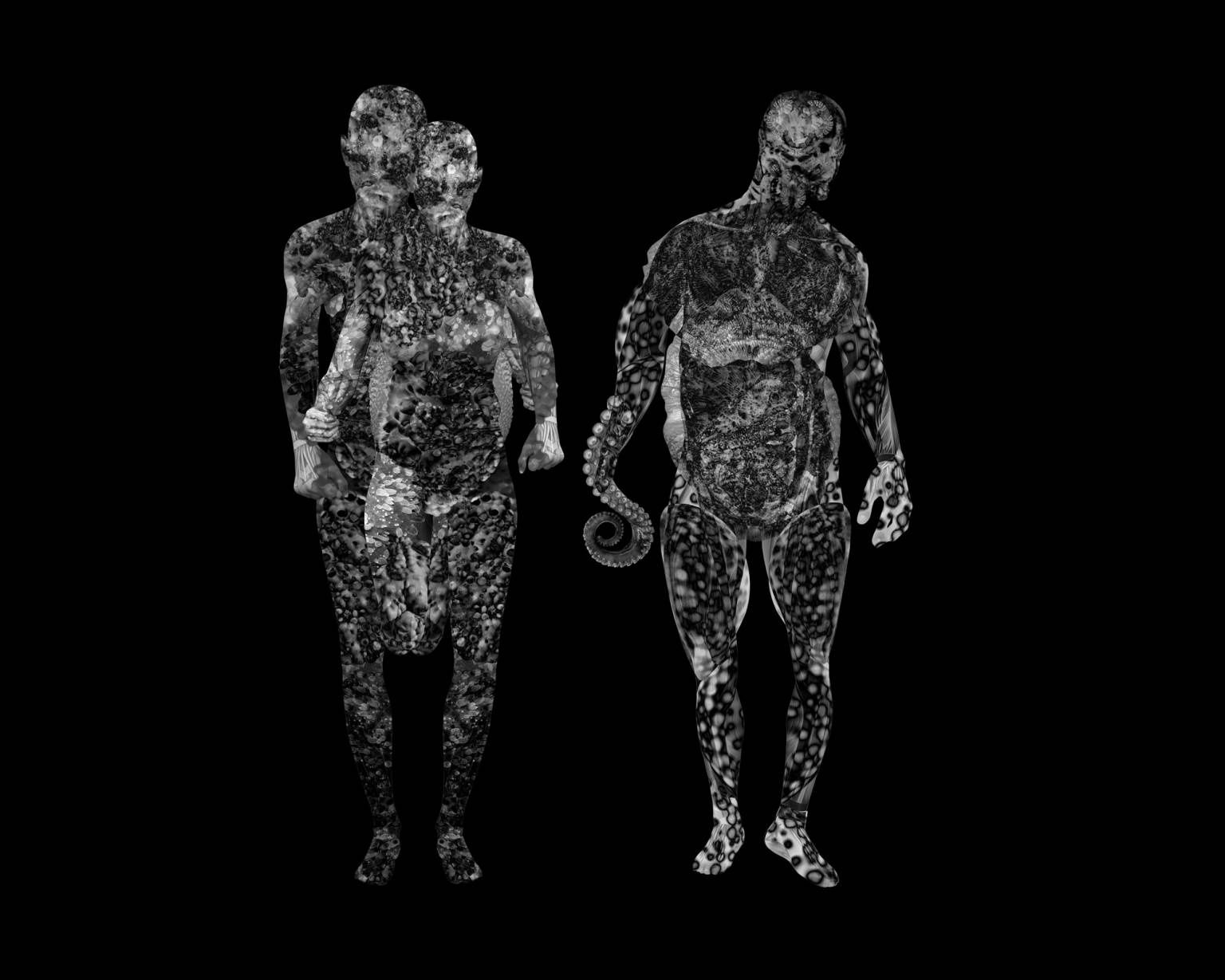

In her immersive video exhibition CYBOTAGE at San Francisco’s Catharine Clark Gallery, Zeina Barakeh examines military technologies that interact with the body, including neuroenhancements for soldiers. The powerful floor-to-ceiling figures in the black-and-white projections resemble the huge guardian statues of ancient Egypt. Their bodies contain images of organic material like shells, coral and octopus tentacles, hinting at how military technologies are often inspired by nature. The ominous figures are both anxiety-producing and intriguing.

Barakeh’s interest in this subject matter stems from her upbringing in Beirut, where she lived until her 30s; she moved to California to attend the San Francisco Art Institute in 2006. In CYBOTAGE, she grapples with the ethical implications of blurring the lines between human and machine, and the use of artificial intelligence in war.

Barakeh recently completed her master’s degree in global security at Arizona State University, where she is a visiting art professor. She is also currently pursuing a PhD in philosophy at the European Graduate School in Switzerland.

KQED spoke with her about the evolution of her art practice, and how she processes the horrors of war through her art.

What did you study at SFAI?

I was painting, and they were very visceral. I changed from working on boards and canvas and rectangular shapes into making cut-out figures larger than life-size and posting them on the wall. The wall basically became my canvas, and I would reorganize these figures. The figures that I made back then are very connected to what I do now. It’s like I made a full circle. I went back to these figures on some level.

All those figures were women. They were dismembered and distorted, and they looked like they had gone through war. They represented my own experiences. It was a way to process my own experiences of living up to my mid-30s in wars. The bodies of these women, the patterns on them — I didn’t use color, it was just black. They were a little bit like drawings on unprimed canvas. They looked like façades of the buildings in Beirut that were riddled with bullets. They were a direct representation of these experiences, and they represented the scars of war for me. The figures — I was very attached to them. They had names. They kind of represented imaginary people that have gone through these wars.

A still from Zeina Barakeh’s ‘The Labyrinths of Remedies,’ 2025. The animation is also on view at Catharine Clark. (Courtesy of the artist)

What made you change to video?

In my last semester at SFAI, I started feeling like all the complexities of warfare could not be encapsulated in these paintings, like I needed more. This is what drove me to time-based work. This is what drove me to do animations. I started doing stop-motion animation because that was the easiest way to learn how to make it on my own. I was just hanging out with the film students, and some very kind peers helped teach me. “Okay, here’s an object. Take a picture, move it. Take another picture. Move it again. Take a short picture,” and so on. Since 2008 basically, I’ve been making animations, and then I perfected my own language of making animations and digital collage.

What made you decide to study global security and philosophy?

It was in 2020, and timing was significant. It was in the middle of the SFAI shutdown. It was watching an institution kind of disintegrate. I have enormous attachment to this institution, to this place, to the people who work in it, because they’re all I know in the U.S. I came to San Francisco because I studied at SFAI, and then I started working there; I spent my entire career working at SFAI.

It was the pandemic, and for me, it was a repeat, on some level, of life in Beirut during war, where you could not leave your house. Of course, here you didn’t have bombs falling over your head, but there were restrictions that you couldn’t bypass. The biggest common factor was lack of resources. You didn’t have access to certain things.

A still from Zeina Barakeh’s ‘CozyCalafia APT47,’ 2025. (Courtesy of the artist)

These were the big factors that made me think, “Okay, what do I want to do at this stage in my life?” And then I realized that I want to learn. That this is the most important gift one can give themselves is to learn. I mean, of course, we learn every day, but to actually go back to school and have a structured kind of learning and earn a degree at the end, that’s like a gift to myself in the form of self-care. It was a way for me to really use it as structured research for my artwork. So, I enrolled in two programs. One was the MA in global security at Arizona State University, and the other one is a PhD at the European Graduate School, which is based in Switzerland.

At Catharine Clark Gallery, you talked about how the two sort of balance each other out. Could you say more about that?

Global security as a field is as far as can be from art, right? It’s about warfare. It’s about politics. It’s about security on all levels, for environmental warfare, competition with other nations. This was a completely unfamiliar field to me, and I was terrified to be in this program. You know, I’m a Palestinian Lebanese woman who grew up in Beirut during a lot of conflict. All my life, I’ve experienced war from a civilian point of view, and I understand how the laws break down during warfare. There are no laws, basically.

So going into that field, it’s very unfamiliar. A lot of my peers serve in the army. Many of my professors were in the military and are connected to the U.S. Department of Defense or have experiences in that field. And on the other hand, the PhD at the European graduate school, which is in philosophy, the vision of that school was also a very unfamiliar field because it’s about philosophy and ethics. OK, it’s connected to art, but it’s also something that I had no foundation in. So for me, I deliberately chose those two programs as a way to keep me grounded in the ethics that relate to warfare.

Zeina Barakeh, ‘CYBOTAGE’ (detail), 2025; animation still, 4:20 minutes. (Courtesy of the artist)

How did you decide on the figures you made for CYBOTAGE that are projected on the wall?

I’m right at the beginning of this shift with my artwork. It’s going from linear narratives of warfare to thinking more about the body. With this first iteration of the work that I created, CYBOTAGE, where I made figures, I have chosen not to create figures that are riddled with technological devices. Instead, I used organic material and material from nature. So these figures are created using seashells, and corals and jellyfish and fish parts, and there’s a lot of layering.

The reason behind that is, ultimately, all these enhancements are inspired by nature. When the soldiers are having sensory enhancement to smell better, to hear better, they go back to animal creatures that smell better than humans and hear better than humans, that see better than humans in the dark. In warfare, swarms of drones are created by the military, and the swarm is basically a group of drones that function together. They can be very small, they can be large, but then each component is like a group of birds traveling, and each drone has its own AI system. They can do multiple things differently, like a combat unit in a way. But the swarms are derived from schools of fish, from swarms of birds, and other forms of life. That’s how I wanted these figures.

They are also meant to have bioluminescence like jellyfish. The shells are protective, they function as exoskeletons. And the corals — I imagined that they replace the bone structure in the body over time. This is the way I imagine these bodies, and they also have a sense of history as well. They look both ancient and futuristic at the same time, and in a way for me, this symbolizes the human quest to always dominate nature, and this quest for longevity and immortality.

‘CYBOTAGE’ is on view at Catharine Clark Gallery (248 Utah St., San Francisco) through May 24, 2025.