It's this stark contrast between nature and urban development that makes PAMM's latest exhibition particularly apt. "Spirit in the Land," which debuted on Wednesday, March 20, and is on view through Sunday, September 8, examines humanity's relationship with our planet through cultural practices. Exhibiting artwork in several mediums from a global crop of artists, including art world stars such as Terry Adkins, Hew Locke, Carrie Mae Weems, Firelei Báez, and Wangechi Mutu, the show attempts to illustrate how solutions to the human-made climate crisis may already exist in how different cultures relate to their environment.

"The way that the natural world — the lands, the water, flora, fauna — informs our sense of self and who we are," says Trevor Schoonmaker, the show's curator. "It shapes our identities as individuals, as a community, as a culture, and in ways that sometimes we're not even really conscious of. I mean, it just informs everything: our spiritual practices, our cuisine, our rituals, recreation. And so the goal, really, is to remind people that we are part of this larger ecosystem. It's not separate from us; it's not something out there. We're not actually trying to save the Earth; the Earth is trying to save us."

The show focuses particularly on artists and communities from the Americas and the Caribbean, examining how indigenous and formerly enslaved communities have existed within and alongside the lands they inhabit. South Carolina-born, Washington D.C.-based artist Sheldon Scott, for instance, excavates his own Gullah Geechee ancestry in his video piece Portrait, number 1 man (day clean ta sun down).

For more than 12 hours, an entire workday for his enslaved ancestors, Scott filmed himself harvesting rice on the former Brookgreen Gardens plantation in South Carolina, painstakingly peeling each grain from its husk. A pile of the one-time cash crop, which was more valuable than cotton and much more labor-intensive to produce during the era of slavery, is neatly placed on a rectangular plinth under the screen, with each grain representing an "unknown, enslaved identity."

The durational nature of the work and Scott's intense focus on the performance led to some surprising moments, some of which didn't become apparent until after filming had concluded. At certain points in the video, grasshoppers land on his shoulder, and a crane wanders through the background behind the artist.

"There were so many times where the human body just became a part of the natural landscape and was not disruptive," says Scott, "and that was a very unique experience for me, being a human being walking into this space, and all of a sudden."

Some of the most affecting artworks in the show, rather than focusing on harmonious coexistence with nature, relate to the ways humanity has already irreparably damaged our home planet.

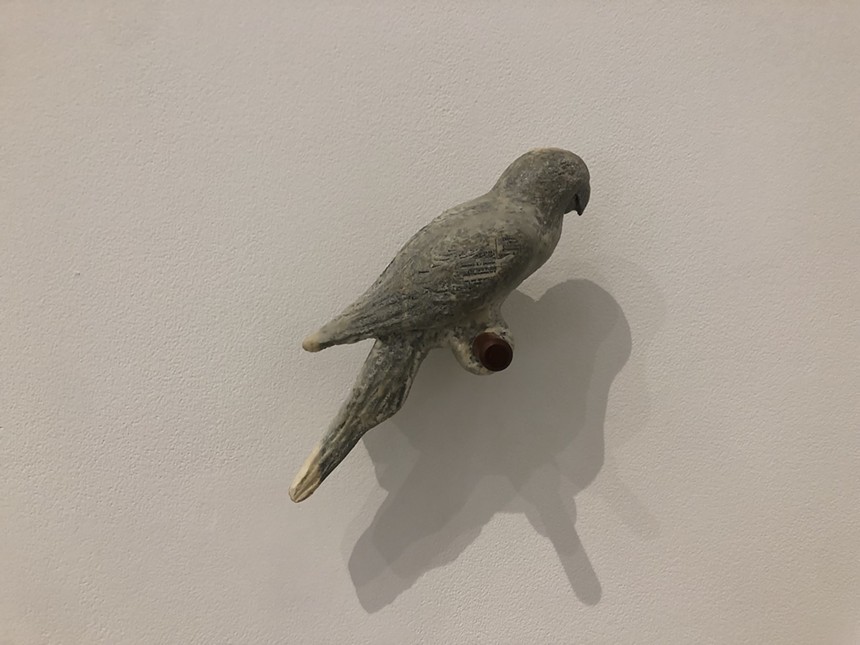

In North Carolina-based artist Mel Chin's installation Never Forever: The Cabinets of Conuropsis, birdsong from the Carolina Parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis) emanates from two specially built speakers painted to resemble the parrot's plumage. But aside from a wax model, there's no bird, and there hasn't been for more than a century. The last Carolina Parakeet died in 1918 after the species was hunted to extinction for its feathers, and no recordings exist of its song. Chin synthesized the sounds using research conducted by biologists on what the bird might have sounded like.