UCLA’s Hammer Museum unveils a landmark exhibit of art-world renegade David Medalla.

Among the institutions that dominate the U.S. art market—museums, auction houses, art fairs, and galleries—the list of confirmed stars of Asian descent is getting gratifyingly long. Anish Kapoor, Martin Wong, Sarah Tse, Nam June Paik, An-My Lê are just a few.

But artists of Filipino descent? To be sure, Paul Pfeiffer and Stephanie Syjuco have landed solo shows at blue-chip New York galleries and placement in blockbuster exhibitions, as Syjuco did recently in the Guggenheim’s recent, all-star “Going Dark.” But as a queer Filipino American writer and artist myself, in search of my own place and voice, Pfeiffer and Syjuco seem like beacons, bright spots in a yawning chasm.

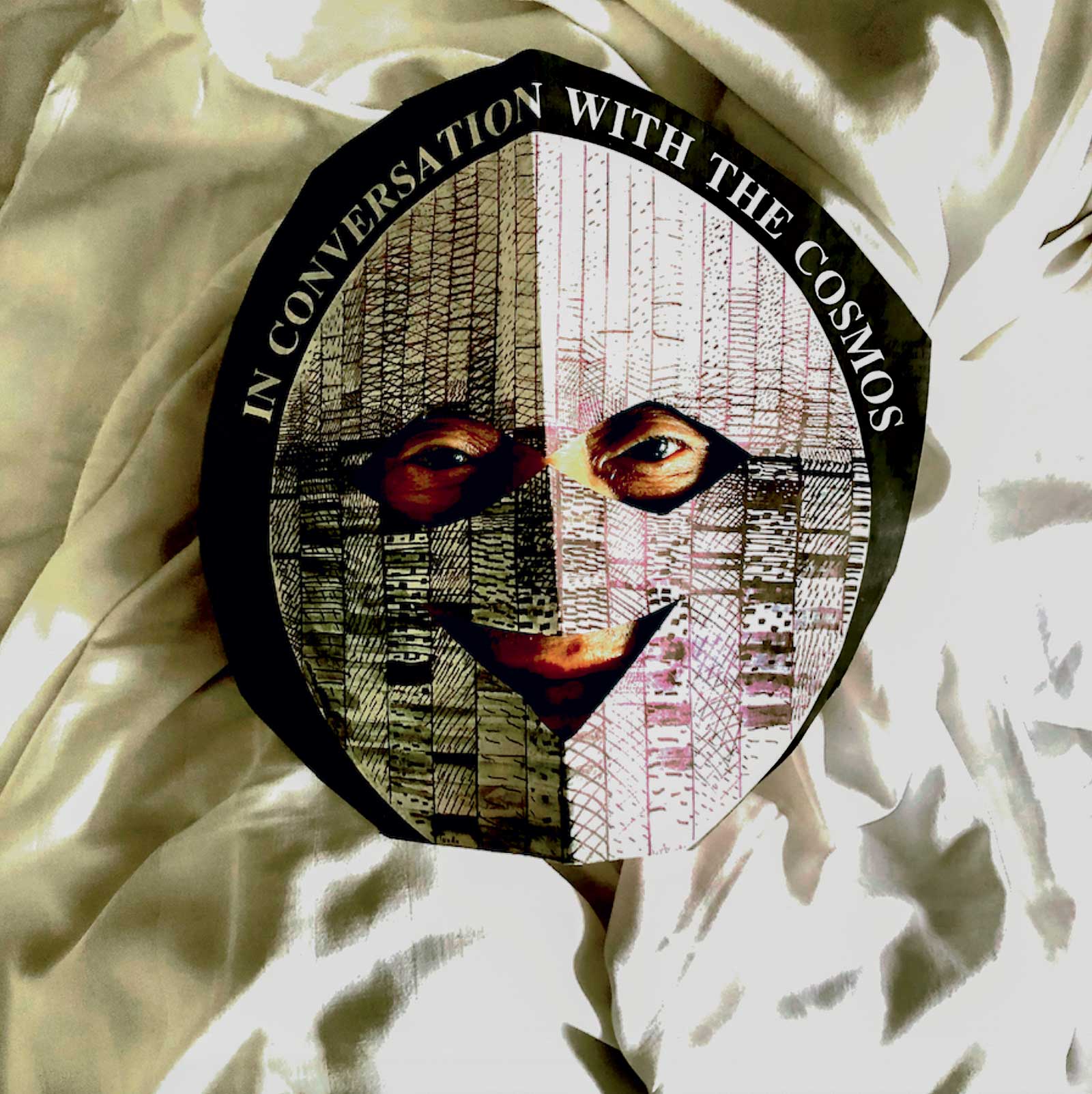

A few enterprising American museums have begun to redress this absence. In 2022, the Newark Museum devoted its special exhibition galleries to the work of San Francisco-born Carlos Villa (1936-2013), whose work encompassed painting, mixed media, and performance. The monumental, quilt-like paintings of Pacita Abad (1946-2004) are currently casting several rooms at the Museum of Modern Art’s PS1 outpost in the glow of their folkloric energy and color. And on June 9, UCLA’s Hammer Museum opens a solo showcase of the wide-ranging work of David Medalla (1942-2020), “In Conversation With the Cosmos.”

Medalla, born and educated in Manila, hit his stride in 1960s youth-quake London. Pop, conceptual, and performance art were all the rage. Medalla co-founded a gallery, Signals London, which championed artists from around the world, including Lygia Clark (Brazil), Jesús Rafael Soto (Venezuela), and Takis (Panayiotis Vassilakis, Greece). Gay, in his early 20s, radiating a lithe, sylph-like beauty, Medalla counted several of the era’s luminaries as friends. “He was going around with Yayoi Kusama at an art event,” recalls collector and close friend Lito Camacho. “She told him to hurriedly change direction with her. She wanted to avoid Yoko Ono, whom she did not like.” That might have been challenging with Medalla—John Lennon was also a friend.

The chronology of how Medalla wound up here from his happy childhood in Ermita seems as fanciful as it is circuitous. One anecdote in The Life and Art of David Medalla, a book published in 2012, seems prophetic: when he was a high school sophomore, he went missing for three weeks. His family discovered he’d been a stowaway aboard an American passenger ship, the SS President Wilson. While at sea bound for Hong Kong, the crew found the teenager—fast asleep.

The story seems to presage Medalla’s arc as an artist—driven by irrepressible curiosity, energy, and a constant need to move, but not necessarily with a clear end-goal or through-line. The journey seems the point, and the glory of his work, but also possibly the drawback. He doesn’t seem faithful to any medium. Drawing, painting, performance, assemblage, poetry, photography, collage, and installation all figure in his work, spanning half a century.

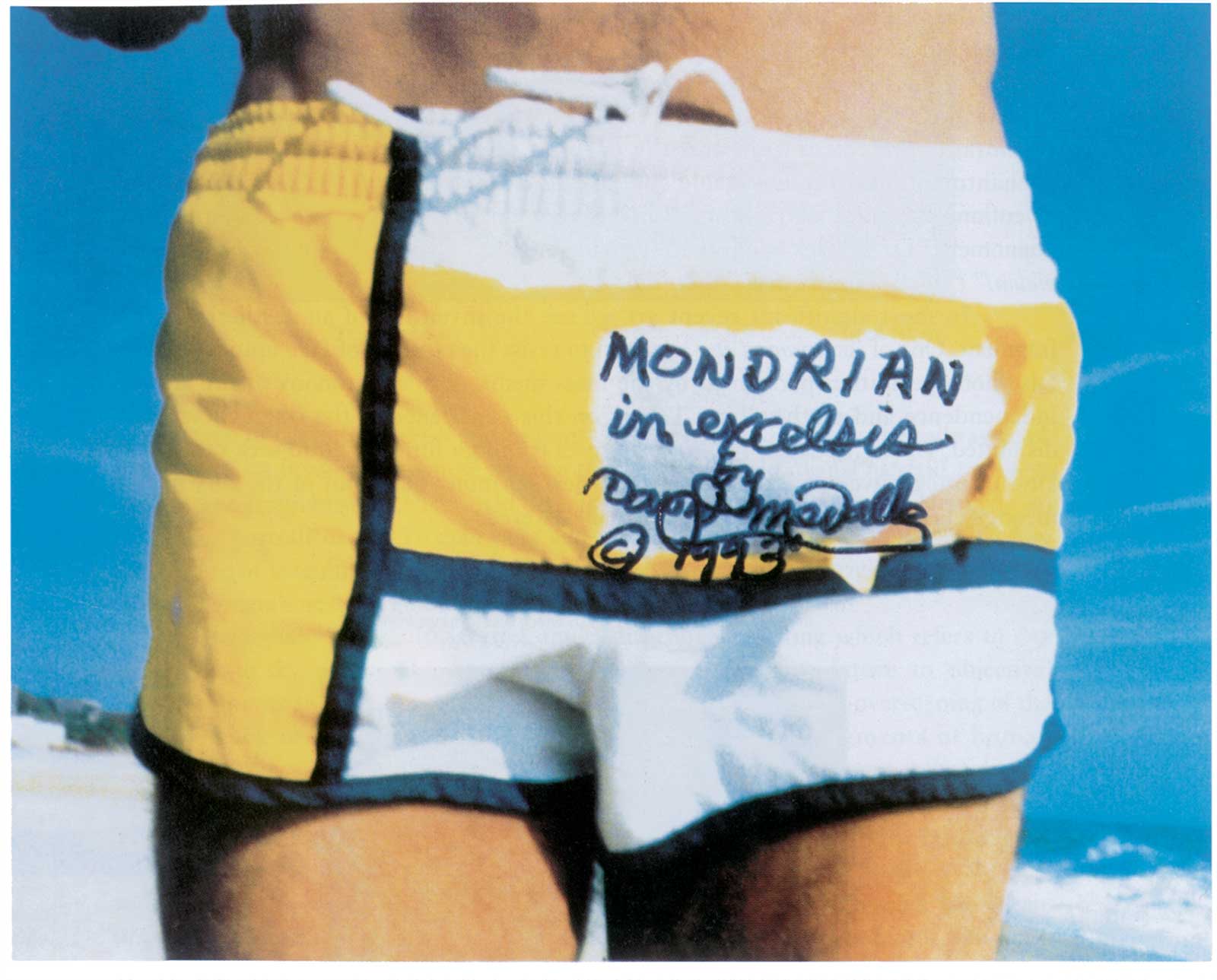

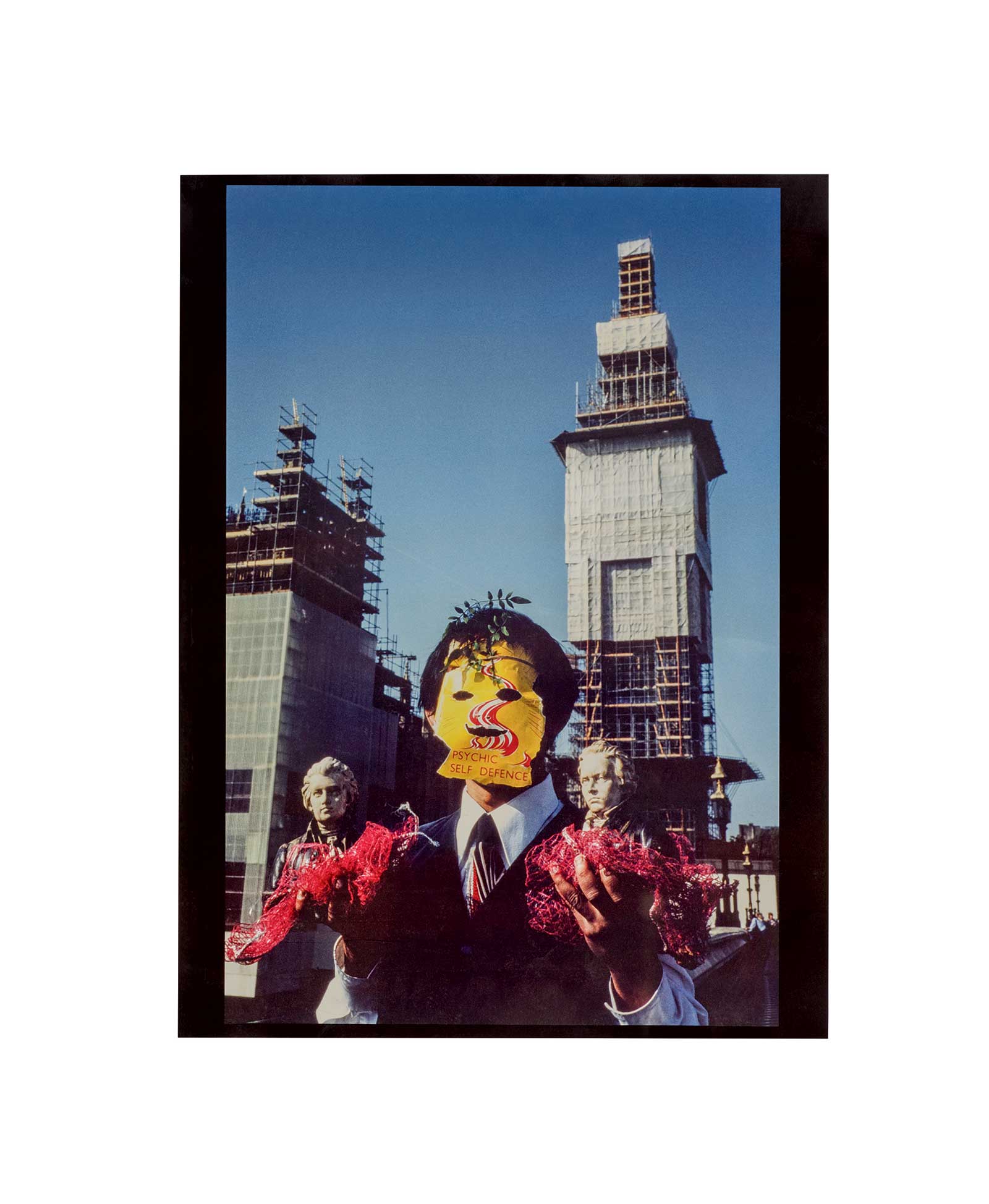

Also evident are the influences of other artists. A quirky, double-face ink portrait of Medalla’s from 1957 (he was around 15 at the time) gives art-school Picasso. “Lava Machine,” an abstract acrylic from 1962, ripples with the energy of Francis Bacon’s biomorphic distortions. Two decades later, “Psychic Self Defense,” a 1983 photo self-portrait, shows a masked Medalla posing with historic, miniature busts (is that Beethoven? Or Alexander Hamilton?). The work clearly echoes the droll self-portraits of two other face-obscuring queer photo artists, Tseng Kwong Chi (Mao jacket, dark glasses) and David Wojnarowicz (paper mask of Rimbaud’s face).

What’s not in question is that Medalla was a pioneer, particularly in the realms of kinetic art and participatory art—fancy language, respectively, for art that moves and changes over time, as well as art which invites active input from the audience. Medalla is best known for his Cloud Canyons, large sculptures which, through trickery of mechanics and tubing, produce elegant, thrusting columns of bubbles. Much admired by Dada titans Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray, one of the Cloud Canyons sculptures is now in the Tate Britain’s permanent collection, while Cloud Canyons No. 31 is on permanent display at the BDO headquarters in Ortigas, acquired in 2019 by Mara Coson, who oversees the bank’s art collection.

Lito and Kim Camacho, who hosted Medalla and his husband, artist Adam Nankervis, in Laguna and Makati during the artist’s final months, also have one of the bubble machines in their collection. It’s displayed at home in conversation with a video performance of their daughter Bea crocheting herself into a white cocoon for 11 hours. Camacho recalls how Medalla, despite failing health, was so taken with their large pet sulcata tortoise, Darwin, that he drew several studies of him in preparation for a project that he was not able to realize.

What’s equally beyond debate about Medalla is his faithfulness to the Philippines. Despite living many years in London and New York, the artist, an outspoken critic of the Marcos regime, never gave up his Philippines passport, and returned to the country to spend the last years of his life.

The Hammer retrospective casts a lens onto Medalla’s place in late 20th century art, a history which has sidelined him, but which he may have also eschewed. Roving restlessly between media, subjects, and approaches, his visual language evolved constantly, in a system that rewards the consistent vocabulary, and the name recognition, of a Basquiat, a Chuck Close, or a Mickalene Thomas. Medalla resisted “museumification” of his work, says the Hammer Museum’s interim chief curator Aram Moshayedi. “I can’t imagine Medalla being pleased by our attempt to situate his work in a historical context, or our desire to better understand the long arc of his career.”

The Hammer retrospective aims to correct skewed assessments of Medalla’s work. “I remember an art historian, who shall go unnamed, telling me that it would be difficult to write about Medalla because he made so little art,” he says. As the exhibition’s breadth, density, and variety show, nothing could be further from the truth. “I think we are only now starting to understand Medalla’s contributions to art history.” His legacy, like his work, is kinetic.