By Max Blue

San Francisco is an often inhospitable city for visual artists to live and work. It’s also birthed major artistic movements and The City is still home to artists whose work reflects their choice to stay. But what sets it apart from the nation’s major art hubs, such as New York and Los Angeles?

It is decidedly not a major hub of the art market.

In the 1930s, San Francisco was a major site of leftist murals funded by the New Deal-era Public Works of Art Project. In the 1950s, when New York was creating the beginnings of a globalized art market by positioning abstract expressionism as the American avant-garde, the Bay Area figurative movement — a group of formerly abstract painters — returned to its representational roots, an East-West split that anticipated their persisting distinctions.

Both the Public Works of Art Project and the figurative movement stemmed from a kind of social realism, an artistic movement emphasizing the working class’ sociopolitical realities. The first was explicit in its content, while the second enacted these artistic values in its insistence on representing everyday people and oppositional stance to market trends.

This spirit of difference and resistance continued through the 1970s and ’80s, with the funk movement, performance art and social practice, and through the dot-com booms with the Mission school in the ’90s and early 2000s.

When Jenifer Wofford was coming of age in The City’s art scene in the ’90s, she said, “people were making meaning in their lives in the arts outside of centers of power.”

“So many artists of diverse backgrounds were getting a more critical toehold, and some of that was because the market had bottomed out so there was more of a level playing field,” she said.

But with the rising cost of living that accompanied the influx of tech to The City, the creative class has struggled to maintain a foothold.

Cheryl Derricotte, who has lived in San Francisco since 2011, equates the experience to working “two full-time jobs.” Many San Francisco artists hold day jobs to supplement or support their art practices.

“You are always splitting your time between a job and a career where you’re not being paid a living wage,” said Trina Michelle Robinson.

Derricotte and Wofford said they combine income from teaching at universities with individual grants and commissions. Robinson said she is currently a substitute teacher for the San Francisco Unified School District following a lucrative stint in tech that helped finance the early years of her artistic career.

“It really is a patchwork quilt to make it happen as a professional artist,” Derricotte said. “San Francisco artists are tireless.”

But these issues aren’t endemic to San Francisco. Fifty-seven percent of New York artists responding to a survey published earlier this year said they made less than $25,000 annually, and Los Angeles isn’t much better. Many artists who remain in The City say they do so out of necessity.

A still from Trina Michelle Robinson’s “Revival” shows a picture of her great-great uncle, William J. French. Courtesy of Trina Michelle Robinson

Robinson’s ancestral connection to The City has long been a focus of her artwork. Her great-great-uncle William J. French, a veteran who is buried in the Presidio, is the subject of one of her films and continues to be a major inspiration.

“My proximity to him is the foundation of my art practice and I don’t feel that it’s possible for me to leave and create the way that I am,” she said. “But it’s hard.”

She’s currently a member of 3.9 Art Collective, named for the predicted percentage of Black San Franciscans prior to the release of the 2010 U.S. Census. While the latest Census data pegs the share at 5.7%, the collective currently has only three active members.

Cheryl Derricotte’s “The Geography of an Artist,” pictured in 2023 at the Museum of Craft and Design, Henrik Kam.

“I see the numbers dwindling and I’m not going to be forced out,” she said. “I’m going to continue that history of African American presence here.”

Similarly, Derricotte said that “not being a San Francisco native, I have stumbled upon great stories that have informed my art practice.”

Her recent exhibition at re.riddle focused on Mary Ellen Pleasant — The City’s first Black landowner and California’s first Black millionaire.

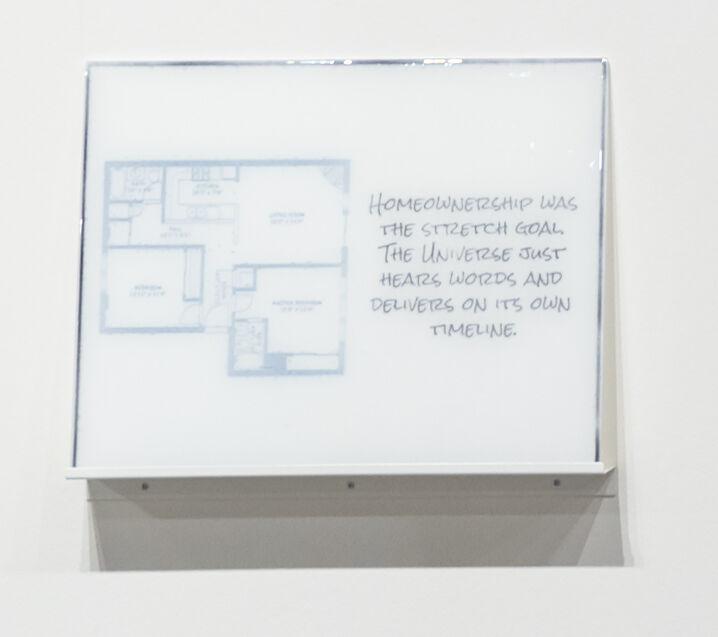

Derricotte said her contribution to the Museum of Craft and Design’s 2023 exhibition “Fight and Flight: Crafting a Bay Area Life” exemplified her “struggle to maintain appropriate, affordable housing over my years of being here.”

The piece, “Geography of an Artist,” featured four glass panels decorated with the floor plans of the four different San Francisco homes in which she has lived, documenting her journey from renting a cluttered loft to owning a home.

Derricotte curated an April exhibition at San Francisco Art Fair titled “We Didn’t Get the Memo” in response to recent murmurings of The City’s art scene drying up and continuing the recent trend of art fairs reinvesting in local communities hosting them.

“The conversation is so much richer than people consider when they just want to talk about our galleries not selling as well as New York galleries,” Wofford said.

Wofford was born in the Bay Area but did not grow up here, moving back when she was a teenager and attending the now-defunct San Francisco Art Institute.

Her artwork also examines local history. “Pattern Recognition,” her recent mural on the Hyde Street side of the Asian Art Museum, celebrated the legacy of The City’s Asian American artists such as Bernice Bing and Carlos Villa. She’s currently working on a project about San Francisco-born diver Vicki Manalo Draves — the first Asian American Olympic gold medalist — for SFMOMA.

“Why are we wasting our time feeling inferior to whatever sad-sack, 19th-century thing is happening on the East Coast?” Wofford said. “The market is not the only game and never was. The Bay Area has so many forms of artistic expression that exist outside of market value.”

This kind of locality might not translate to a bigger stage, but maybe that’s the point.